In this blog post, we will investigate and explore ways in which we can understand and conceive of what we are. We will see how, although we don’t always notice it clearly, we have implicit conceptions of reality; we will investigate how they manifest themselves and the effects they can have on us. We will discuss the importance of good epistemology related to the subject of personal identity as well as its more general importance. We will explore 3 views of personal identity proposed by Daniel Kolak: closed individualism («I am this individual / person / animal…»), empty individualism («I am this moment of experience»), and open individualism («all beings are actually one»). We will discuss about which of these visions fit the most with reality, argue about their ethical importance, talk about what they can tell us about existence and end by exploring interesting and perhaps useful ways in which we can look at and mix these visions.

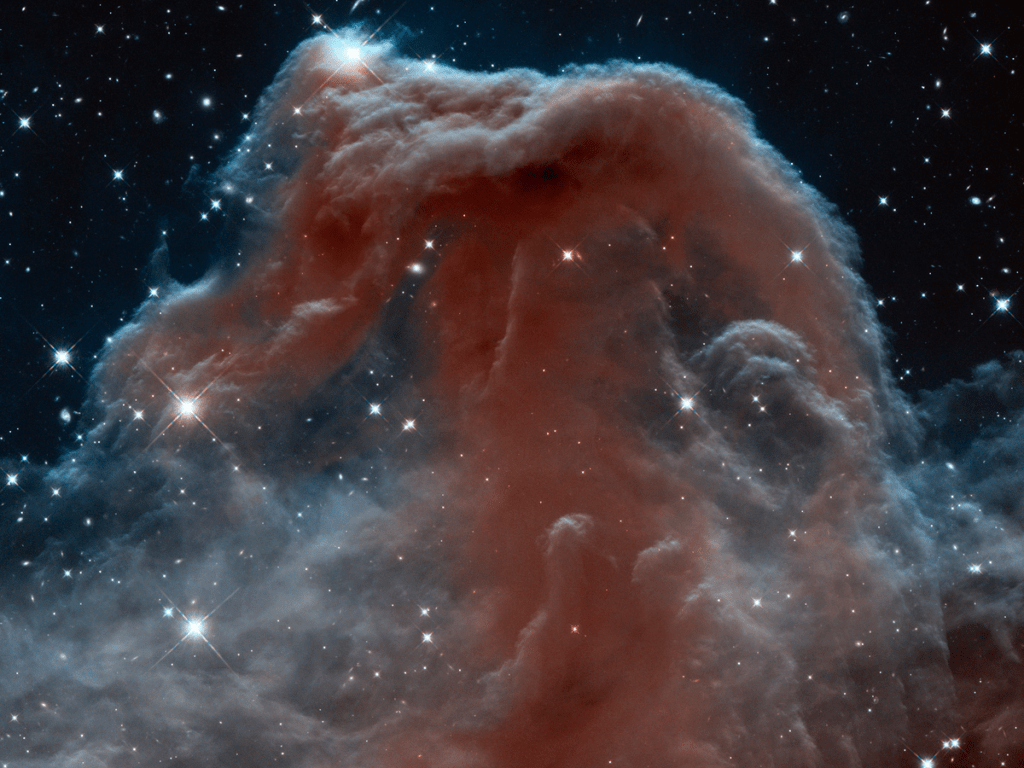

Graffiti that I found at the universidad nacional «we are only one consciousness»

We have implicit conceptions.

If we are asked what our conception of something is, in many cases we will first imagine them in the form of words as well as explicit descriptions, «I believe that the earth is a planet that orbits around a star that we call the sun» «I believe that a star is a gigantic ball of plasma where fusion reactions occur that release energy». However, explicit descriptions are not the only way in which we experience conceptions about what something is; when we imagine, for example, a chair, there exists as part of our mental representation of it something (perhaps a texture? perhaps a vibe?), that tells us «this is a chair». In the same way, when we think of someone, there is something in their representation that says «this is [the person we are thinking about]». These ways in which our experiences communicate about their content, in which we conceive of things, have / transmit other characteristics as well, such as how much we like or dislike them, a relationship with other representations, etc.

As we will analyze later on, our implicit conceptions (as well as all of our understanding of reality more generally!) are extremely important ethically due to the effects that they can have on the way we act and the ways in which these are real and in many cases really negative or positive.

It is also important to keep in mind that in many cases, implicit conceptions that feel true, aren’t really so (something that we can in many cases verify beyond reasonable doubt).

Qualia, propositional qualia, ontological qualia.

This word refers to the range of ways in which experience presents itself. Experiences can be richly colored or bare and monochromatic, they can be spatial and kinesthetic or devoid of geometry and directions, they can be flavorfully blended or felt as coming from mutually unintelligible dimensions, and so on. Classic qualia examples include things like the redness of red, the tartness of lime, and the glow of bodily warmth. However, qualia extends into categories far beyond the classic examples, beyond the wildest of our common-sense conceptions. There are modes of experience as altogether different from everything we have ever experienced as vision qualia is different from sound qualia.

Definition of qualia, from the glossary of the qualia research institute

These «something», which tell us things about what we are representing in our experience, which hold implicit conceptions, are also a type of qualia. Andrés Gómez Emilsson calls them propositional qualia. There are propositional qualia that tell us «mundane», «day to day» things, but in the same way there are propositional qualia that go deeper (and a great variety of them), that contain information of our implicit conceptions about the nature of reality and of who we are, etc. Andrés calls this type of qualia, ontological qualia.

At the most basic level, an ontology is an account of what is real and what exists.

Definition of ontology, from the same glossary.

If we ask ourselves the question of who we are, answers emerge then in the form of these ontological qualia. Perhaps I feel that I am Arturo, that I am my body, that I am the moments that I remember, that I will be the moments of my future, we identify with something. There is a very wide range of possible ways to conceive of what we are and to feel it.

How do different ideas about the fundamental nature of reality feel? Is everything atoms? Is everything fields? Is everything qualia? Is everything transformations that can be done to zero? How can we not to suffer because of our ontologies? In this meditation on ontologies Andrés Gómez Emilsson explores these issues.

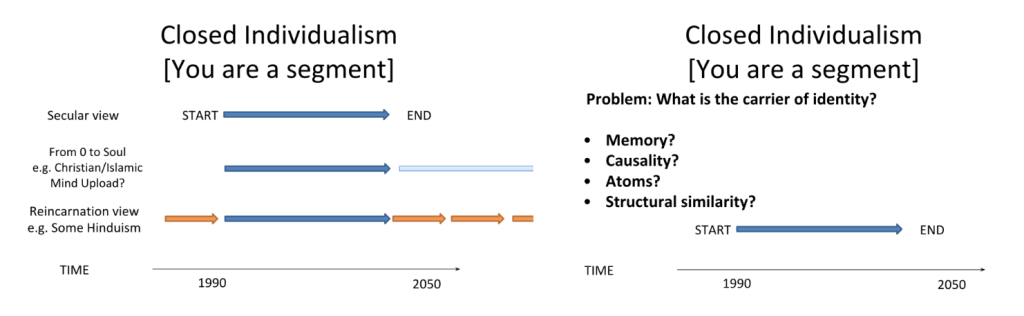

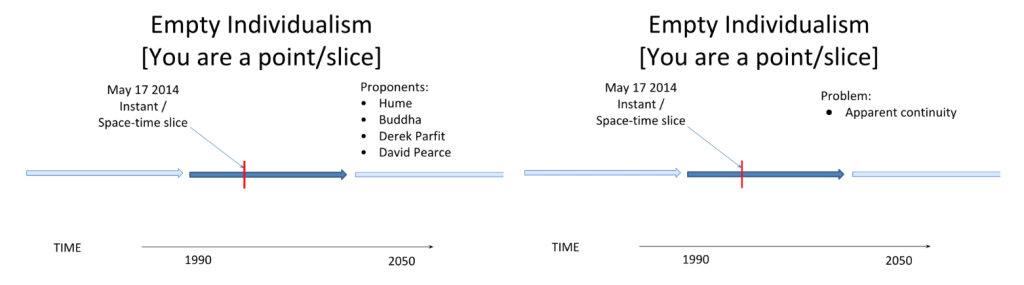

Our ancestors were selected by evolution to mostly identify with the «individual» (or let’s call it person, or animal, etc.) that they «are» (or believe they are), causing this same type of qualia to exist in most current human beings. We run an egocentric representation of the world in our heads. There usually exists in each moment of experience a feeling that says «I am this person». Daniel Kolak called this view of personal identity «closed individualism«. You are a segment, you start to exist when you are born and you stop existing when you die (or after that you continue existing in the afterlife or reincarnation, etc.). However, as we will explore in greater depth later on, there are a great number of problems with this view of personal identity (for example, what is our identity «carrier»? why would the physical systems that we are become fundamental entities or natural kinds?).

Epistemology is very important.

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that studies the nature, origin and limits of knowledge.

Epistemology asks what knowledge is, how it is acquired, what justifies beliefs and how it can distinguish between those that are true and those that are not. Epistemology seeks to understand the foundations of human knowledge and wants to develop criteria to evaluate the validity of knowledge claims in various fields, from science to metaphysics. In order to truly and appropriately understand anything, it is essential that we approach it with a good epistemology. If we do not approach it with it, we will simply get lost and believe that something is what it really is not. Epistemology is like a map and instructions (instructions such as, for example, the scientific method or logic) that guide us towards generating appropriate models of reality.

Images of the goddess of epistemology. She loves epistemology and truth. She recognizes the amazing power that good epistemology has to improve our conditions and looks in awe at this fact. She tries to find intelligent ways in which we can get closer to what is true. She always carries with her a spirit of doubt and does not settle comfortably into beliefs. She tries to find logical inconsistencies and fallacies (which, using tricks, appear and feel as if they were correct), she looks for them in order to solve and heal them with kindness. She loves mathematical proofs and physics experiments. She likes the idea of the purple pill.

The universe and it’s principles are, have been, and will always be there, regardless of our personal aesthetics and beliefs.

The universe follows several principles that shape it, these principles can guide us to find the true nature of reality. Many of them center around things that in a way have great beauty in their simplicity and their patterns. For example, we can derive the conservation laws of a physical system with Noether’s theorem, which tells us that these are obtained from various symmetries. If a system is invariant under translational symmetries then linear momentum is conserved; if it is invariant under rotations, angular momentum is conserved; if it is invariant under temporal translations, then energy is conserved. The standard model of particles is also derived from symmetries.

I say all of this to argue that the way in which we derive the physical constants is perhaps pointing to the fact that, in a way, the universe is not arbitrary and «whatever we imagine», there is something real to discover and understand and it follows precise principles and patterns. In a way, the nature of the universe is similar to the fact that 5+5=10.

When we think about the universe we are thinking about something real. Although what we experience is representations of it, these same representations are referring to something truly existent, it simply «is there» regardless of what we think about it. This same principle applies to our reasoning about personal identity, of course.

«it is what it is»

Water in minecraft has «impossible» behaviors, it can expand and flow infinitely from a single or very few sources, something that real water cannot do. This is possible because minecraft water is not true water but code running on transistors that acts as if it were water, in the same way, we run «programs» / models / ideas in our representation of the universe that although can be felt as extremely true, really are not. A good epistemology allows us to distinguish which of these «programs» point to an external truth and which do not.

Indirect realism of perception, we are moments of experience that adopt the human form and empty individualism.

A very good place from which we can begin to ask ourselves and explore possibilities about what we really are is to analyze the structure of our experience, the way in which it behaves and the ways in which it can behave in exotic states. This importance of exotic states, could we say, follows the same pattern as the fact that, in order to understand many physical phenomena, we analyze their behavior in extreme situations (or at least different from the usual ones of «room temperature»), such as very low or very high temperatures, etc.

Many times, in altered states of consciousness, changes occur in what we implicitly conceive as the external world or as a «direct connection» with it. Exotic geometric patterns can be generated, changes in colors, changes in shapes (not only two or even three dimensional), there can be alterations in sounds and their textures, changes in bodily sensations, there can be synesthesia (for example, experiencing visual qualia based on stimuli that would usually generate auditory qualia) and much more from a very wide variety of exotic effects. The ways in which we can play with the structure of our experience and discover how our brain represents reality are not limited to those induced by psychoactive substances. The clearest example is the states so different from our daily life that we can achieve with meditation. Another interesting example is autostereograms, which allow us to understand how the sensation of depth in our visual field is not due to a direct connection with the outside world, but is generated by our brain through «tricks» that can ultimately be explained by the physics of our representation of reality. In autostereograms, the information that allows our brain to generate an image with depth is encoded on a two-dimensional surface. We can see this image by unfocusing / relaxing our eyes until they settle into a position that allows us to see it.

Autostereogram of a lobster (to see the hidden image we can unfocus / relax our eyes until they settle in such a way that the image with depth is seen)

forest synesthesia by symmetric vision

In many cases, it reaches the point where our experience ceases to be a representation of the world around us and of our self and becomes something else. We could say that it begins to act as a physical system now more independent of the inputs it receives through the senses and of the conditioning that usually gives it its shape, something like that we can see in this replication. There is a very wide variety of very strange states in which we experience extremely different things from our daily experiences: we can experience space without limits, we can experience hyperbolic geometry, and a further very large number of possibilities.

Probably in most human beings, there exists the implicit conception that we directly observe the world (a conception also known as direct realism of perception), that what we have in our visual field (at this moment most likely a technological device), in our hearing, in our proprioception, etc. Is directly the external device, the sound of voices, our body or is anything else that has a representation within our experience. However, if we think about it carefully, the fact that our experiences can be altered in such strange ways should generate a lot of confusion regarding this conception. What is happening? If we wanted to maintain direct realism of perception, we would have to generate very strange and implausible explanations. Are we generating hallucinations on top of our direct perception? But where are these hallucinations? Are we generating them only in the brain? But if so, why do we see them outside? Are we sending them outward? But if so, why don’t others see them?

From cartoon epistemology

Understanding what we are experiencing not as a direct experience of the world but as a representation or simulation of it inside our brains (indirect realism of perception) gives an explanation in much more accordance with the nature of our experience and which can explain the effects of these altered states in a much clearer way.

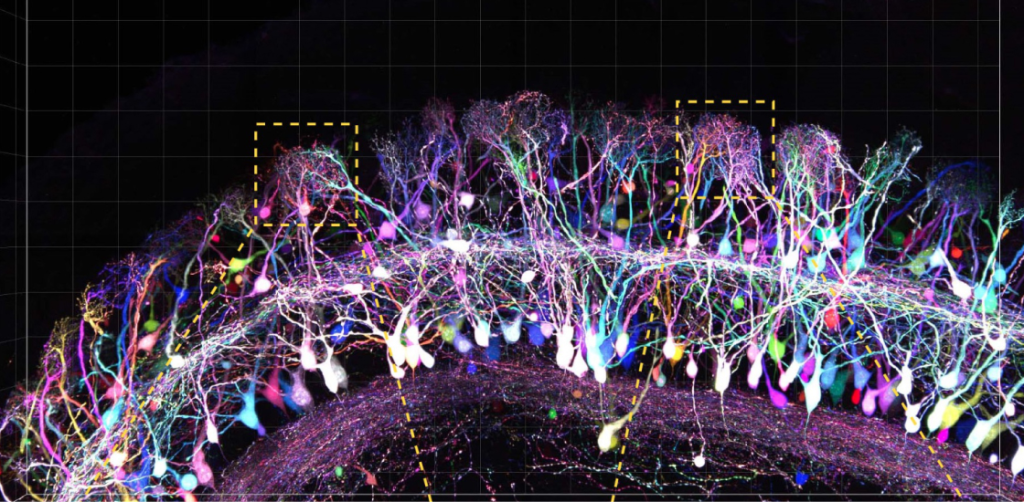

We can thus understand our experience as moments of experience in our brain, which are physical systems made of experience, of qualia. These physical systems were selected during our evolutionary process to take forms that mimic the outside world, to have a sense of self, to have propositional qualia, to make computations, to have colors, tastes, smells, etc. The human body takes signals from the outside world through the senses and converts them into representations / simulations / «reflections» housed in each moment of experience. We could perhaps imagine it as if the brain «folded» or altered the field of qualia to give it all those useful forms that we experience and that we implicitly (and mistakenly) conceive as a direct connection with external reality. In various altered states then, this field takes other less «folded» and simpler forms, or gets folded in other ways, producing experiences very different from the usual ones.

Daniel Kolak calls the view of personal identity that conceives of what we are as moments of experience empty individualism, it differs from closed individualism in the fact that it does not conceive of what we are as the entire segment of our life but as discrete and separate moments of experience. We can see this conception of what we are as something much more coherent with reality than closed individualism, since we can interpret the feeling of unity of all the moments of a lifetime (and the feeling of the passage of time) as a structural characteristic of each of these and not as an ontological reality. According to empty individualism, we are not simultaneously various moments of experience but we are a single one «this one».

Considering ourselves as physical systems that are collections of moments of experience often has (and arguably should have) several effects on the way we act. For example, on our idea of forgiveness (although for this we really only need the part where we are physical systems), in a way the «person» who made the mistake is not the same one with whom we interact afterwards, so why shouldn’t we forgive? (of course this does not mean that we should not put effort into preventing those mistakes from happening again, in fact doing this is tremendously important).

Also the way in which we often rationalize the pain of someone who, for example, has a very bad experience with psychedelics, or any other type of bad experience, where we think that that «person» will benefit later, ceases to make sense, the extremely horrible moments of experience that occurred are simply there, they do not benefit and will never benefit.

Time

The idea of empty individualism (and ideas of personal identity more generally) is closely related to our conception of time. There are several ways to understand the ontological nature of time, these have great power to define the way in which we conceive of reality and in which we act. There are two particularly relevant ways of conceiving time, the first one is presentism, which is in accordance with our intuitive idea of time, only the fleeting present exists, the past is only a memory and the future only exists in our imaginations, and the second one is eternalism, which says that the past and the future are as real as the present, they are actually like «other places» only that instead of us being distanced from them only through 3 spatial dimensions, we are also distanced by a fourth: time. All moments exist, have always existed, and will always exist.

Arguments in favor of eternalism are usually based on Einstein’s relativity, in the past it was thought that there was a kind of metronome that would tell the entire universe what moment it was. However, with relativity, we discovered that different frames of reference in spacetime have different planes of simultaneity (something that may seem simultaneous from one frame of reference, from one «perspective», is not from another), there is no absolute line of the present, there is no single present. Models of relativity therefore model time and space as a four-dimensional continuum. A more precise argument based on relativity in favor of eternalism is the Rietdijk-Putnam argument.

Joining the idea of empty individualism with that of eternalism, we would then have an ontology of the universe where all moments of experience simply «are there», have always been there and will always be there, while being separate. Our notion of the passage of time can also be understood from an indirect realist perspective, we can understand our sense of it as a structural feature of each moment of experience. Andrés Gómez Emilsson calls this feature of our representation / simulation of the world the pseudo-time arrow and just like with the rest of its features, it can be subject to very significant alterations. For example, as explored in the article of the same name, we can experience moments of eternity, time loops, time dilation, among others.

Universal unity and open individualism.

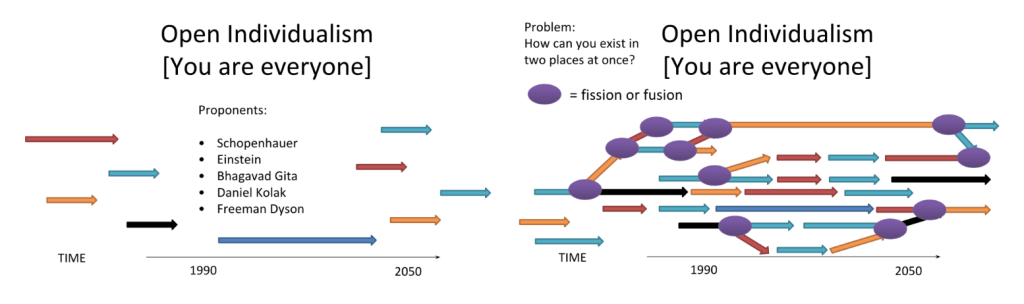

The third view on personal identity described by Daniel Kolak is that of open individualism. In this view, the universe is aproximately conceived as a single structure of qualia, which is segmented at some points generating an illusion of separation. Each being would have moments of experience that although apparently are only their own, share the same universal essence. It can be argued that, if we are willing to accept that we do exist from moment to moment, we would then have to be all the moments of experience in the universe. This, due to the fact that it is extremely difficult to find a «just mine» identity carrier that distinguishes us from being to being (for example, all of the matter and energy that make up our bodies are constantly changing, without there being anything really constant in them). Thus then, we would share the true and only identity carrier, our shared essence, with the stars, with the electrons, with the animals, with the quarks and with everything else.

From physics we have not found anything that can act as such a unique identity carrier either. As far as we know, the moments of experience that we are, are simply another instance of the fields of physics, not something fundamentally different from them, a conception that agrees with the behaviors that our experience follows, which, like any other physical system, acts according to physical laws (for example, it has non-linear wave behavior). If we pay enough attention we can notice that this is the case for common sober states, although this tends to become much more evident in altered states of consciousness (whether produced by meditation, psychoactive substances or any other means).

Moreover, there are ways of understanding physics that actually agree with this idea of universal unity, an example is the idea of the one-electron universe postulated by John Wheeler, which understands the entire universe as manifestations of a single entity. We would then be that entity.

Under Open Individualism, that one electron is you. From every single moment of experience to the next, you may have experienced life as a sextillion different animals, been 10^32 fleeting macroscropic entangled particles, and gotten stuck as a single non-interacting electron in the inter-galactic medium for googols of subjective years. Of course you will not remember any of this, because your memories, and indeed all of your motivational architecture and anticipation programs, are embedded in the brain you are instantiating right now. From that point of view, there is absolutely no trace of the experiences you had during this hiatus.

The above way of describing the one-electron view is still just an approximation. In order to see it fully, we also need to address the fact that there is no “natural” order to all of these different experiences. Every way of factorizing it and describing the history of the universe as “this happened before this happened” and “this, now that” could be equally inapplicable from the point of view of fundamental reality.

Andrés Gómez Emilsson writing about the one electron in this article.

Joining the idea of universal unity with eternalism, we could then understand the universe as a single spatio-temporal structure or field which is composed of all moments of experience.

The solution to the boundary problem of consciousness (article on this topic published in Frontiers, more informal explanation) proposed by the Qualia Research Institute, seeks to understand the way in which this structure, understanding it as a field, is separated into discrete moments of experience as a result of its topology. To a first approximation, we could say that in the same way we can fold a clown balloon to form «monads», which remain part of the same balloon. The universal field gets separated into monads that make up each moment of experience, which exhibit holistic properties that give them computational benefits (a topic too long to cover in detail in this blog post). From this perspective, we can find a kind of harmony between the empty and open views of personal identity, in a way we are separate and in another we are part of the same thing.

When thinking about open individualism we also realize that suffering and its true and in many cases inconceivable horror is not something «separate» from us. In reality, all of it is in a way ours. Of course, on the other side of the coin, all the well-being of the universe is also ours. This fact together with a more detailed investigation of valence that makes us think about its true magnitudes, should motivate us to act.

Open individualism arguably has the ability to cause a before and after in the organization of the world, the feeling of unity together with the rigorous philosophical arguments in its favor have the potential to solve many of the coordination problems and other issues that afflict the world today.

Humans are not a «fundamental something»

Us humans tend to represent ourselves as «fundamental entities», it was much easier in our past for us to represent each other in this simplified way, instead of having a more detailed and realistic vision. Throughout our history there have been several ideas related to this type of conception, such as the idea of vitalism, or various conceptions of the soul. However, if we analyze in a more rigorous way what we know about ourselves through science, we realize that conceiving of ourselves as something fundamental (which usually goes hand in hand with closed individualism) is quite difficult to sustain. We know that our cells are physical systems with great complexity and that they come together to form emergent structures, such as organs, which nevertheless continue to be governed by the same laws of physics that apply on smaller scales (and on larger ones).

Thus we can understand ourselves as extremely complex systems that acquired their form during millions of years of natural selection, but which nevertheless continue to be governed under the same laws of the rest of the universe and are made «of the same stuff» as everything else. Perhaps our extreme rarity and our great intelligence make us «special» in some way, but ultimately we are simply also physical systems, just like neutron stars, just like volcanoes, just like oceans, just like black holes.

Another interesting way by which we can consider the nature of our existence is by taking a kind of «view from nowhere.» We could imagine ourselves looking at the universe to find there a small accumulation of matter, «Earth,» with a temperature and other conditions suitable for the fields of physics to organize themselves through a process of natural selection into systems of very great complexity «life.» Some organizations of these fields of physics formed «brains,» where they generated moments of experience that acted as representations / simulations of reality. In these representations, there was a sense of identification with the system they directed, with the «self». These types of systems, «conscious living beings», had a very large reproductive advantage. Within these beings emerged one with a particularly high intelligence, «humans», who are now discovering their true nature and the true nature of reality.

If the universe is a field of consciousness where are most experiences?

Why all of this matters

Almost certainly we all recognize, at some level, that acting based on wrong assumptions can be harmful. If someone, without having properly checked it, only guessing, wrongly assumes that an airplane is in a state suitable for safe flight, causing it to crash later, harming its passengers, the vast majority of us would accept that this was an unacceptable mistake and that it is necessary for the way in which we interpret the state of the plane to follow a rigorous method that leads us to the truth of its state.

In the same way, it makes a lot of sense to understand that at least some of the mistakes we can make about the reality of what we are and what existence is, can also end in seriously bad results.

Closed individualism, in many cases, causes us to act selfishly, carried away by what our experience appears to be, ignoring «others’» suffering, allowing it to continue to occur or even causing it. Taking an open or empty individualistic perspective (or a harmony between the two, or a harmony joining also aspects of closed individualism), we see the reality of external moments of experience, of our connection with them and of both their suffering and their pleasure under another lens. It also gives us a new sense of urgency.

«My joy is your joy and my suffering is your suffering»

«Do unto others as you would have them do unto you»

We can discover new perspectives, structures and ways of looking at these phrases.

The distinction that we make subconsciously between the self and the other, after considering open individualism, usually gets transformed we «see the soul behind». Now the intention of collaboration emerges.

Looking at it again from a kind of nowhere perspective, we can notice how what is really happening is that in some of these sections of the universe that act as representations of the rest of it, there are implicit conceptions that have no basis in something real and which cause damaging effects. However, now, progressively these sections of the universe (us) are beginning to realize the lack of basis for such conceptions, to let them dissolve and to let what they know about the nature of reality through good epistemology, build more adequate and more beneficial representations for everyone. What will they achieve with something so beautiful? Societies animated by gradients of bliss? The relief from intense suffering for so many beings who for now remain ignored? Experiences orders and orders of magnitude purer, more beautiful and more intense than anything experienced on Earth at the beginning of the 21st century? What is possible for love to mean? Rich and beautiful explorations of the possibilities in consciousness that would make the psychedelia of this very century seem like mere specks?

The «Goldilocks zone» of personal identity.

She points you to the symbols hanging on the walls. “The first three symbols over there represent each of these views. The one with a ring of plants and as many eyes as individual lines represents Closed Individualism. Each being has a different size, shape, and lifetime. Like trees, identities are messy and complicated; each bearing its own unique temporally-extended narrative. The symbol with a large eye in the center and a rainbow represents Open Individualism. It is the consciousness of All Is One, which has a full-spectrum rainbow flavor. And the one on the right is Empty Individualism. Each moment of experience is its own unbridgeable monad, separated from every other monad by the fundamental fire of differentiation.”

Andrés Gómez Emilsson in Burning Man Theme-Camps of the Year 2029: From Replicator to Rainbow God (2/2)

Each view of personal identity has advantages and disadvantages. Open Individualism comes with a solution to the fear of death, but it can also give rise to a kind of cosmic solipsism. Closed Individualism makes us feel fundamentally special, but also disconnected from the universe and fundamentally misunderstood by others. Empty Individualism is philosophically satisfying, but it can come with a feeling of lack of agency and the fear of being a timeslice trapped in a negative place. The Goldilocks zone of personal identity allows us to see the universe as a superposition made of paraconsistent logic of the three views. Perhaps the universe has characteristics of the three. (Definition taken and changed slightly from the glossary of the Qualia Research Institute).

With this type of vision we can simultaneously take the different perspectives offered by each view of personal identity. We can hold a light conception of us as «the person we are» to build ourselves and treat ourselves in a nice way, a particular type of cooperation between moments of experiencia. We can take the perspective of empty individualism to have a serious and adequate perspective on the most unfortunate moments and to understand what is present in our experience. We can take the benefits of cooperation of open individualism as well as its vision on altruism. Perhaps the universe is not simply only one of these.

All this ultimately to keep answering the questions: what is really happening? What exists? What really matters?

Deja un comentario