The way most humans classify what matters usually doesn’t follow what actually does. Our default programming is optimized to track things which helped us reproduce and survive in our ancestral landscape and to «paint them» so that they felt as if they mattered, as if they were the things we actually cared about. They also tend to feel as if we were contacting the actual external thing and its essence. All of this actually isn’t true, our experiences of things are actually internal representations isomorphic to the stuff outside of us. Whenever you see something outside of you, the light it reflects hits your retina, which activates your optic nerve, which sends signals to your brain where a representation is made which is actually what you are experiencing. The same for all other sensations of the «external world». A lot of people say, when asked, that this is obvious, but at many times they don’t necessarily actually get it, or they don’t take that line of reasoning far enough so that it starts affecting the way they act, or they follow it only partially in ways which make them conclude that nothing actually matters, thus also acting in irresponsible ways.

Our brain makes a representation/simulation of reality, thats what we «live» in/are, from cartoon epistemology.

Things (or rather should I say experiences) in the outside of the pocket we are do matter though, a lot. The same way that particles may have charges or matter has different temperatures, I would argue that each experience has a characteristic that makes it feel good, bad or neutral, that characteristic is valence, valence is what builds the pleasure pain-axis. The beautiful smell of strawberries usually has a high valence, the same for joy, while grief or existential dread usually have negative valence, even though someone may say that the experience of seeing, for instance, a particular event happening is subjective and can be different depending on who you ask, or the experience of listening to the same song, or seeing the same object may be better or worse for different persons, making value thus relative, I would argue that that conclusion is just a result of trying to measure value in the wrong way. Value actually lies on experiences, your representation of the holocaust most likely have a negative tone, while the one of someone who supported it may have a positive one, but those opinions don’t change the experiences of those who lived through it, their suffering is still bad. Also we can notice that what makes different representations of the same phenomenon be felt in better or worse ways is the structure of those experiences, and so, if you found a song beautiful one day and a the next one horrible, that actually is caused by the representation of it having different shapes and structures (probably what determines how good or bad those structures are is their levels of consonance and dissonance). Valence is real, horrible experiences are actually, truly horrible and beautiful ones are actually beautiful. This becomes clear to whoever has broken their leg, or to whoever suffers from chronic pain, or to whoever is having an incredible and almost unbelievably intensely love filled experience on MDMA. Another way you could think about this is by noticing that your current moment of experience is «what it is», and is as good, bad or neutral as it is, independent of whatever opinions someone else might hold about it, the same applies for all other moments of experience.

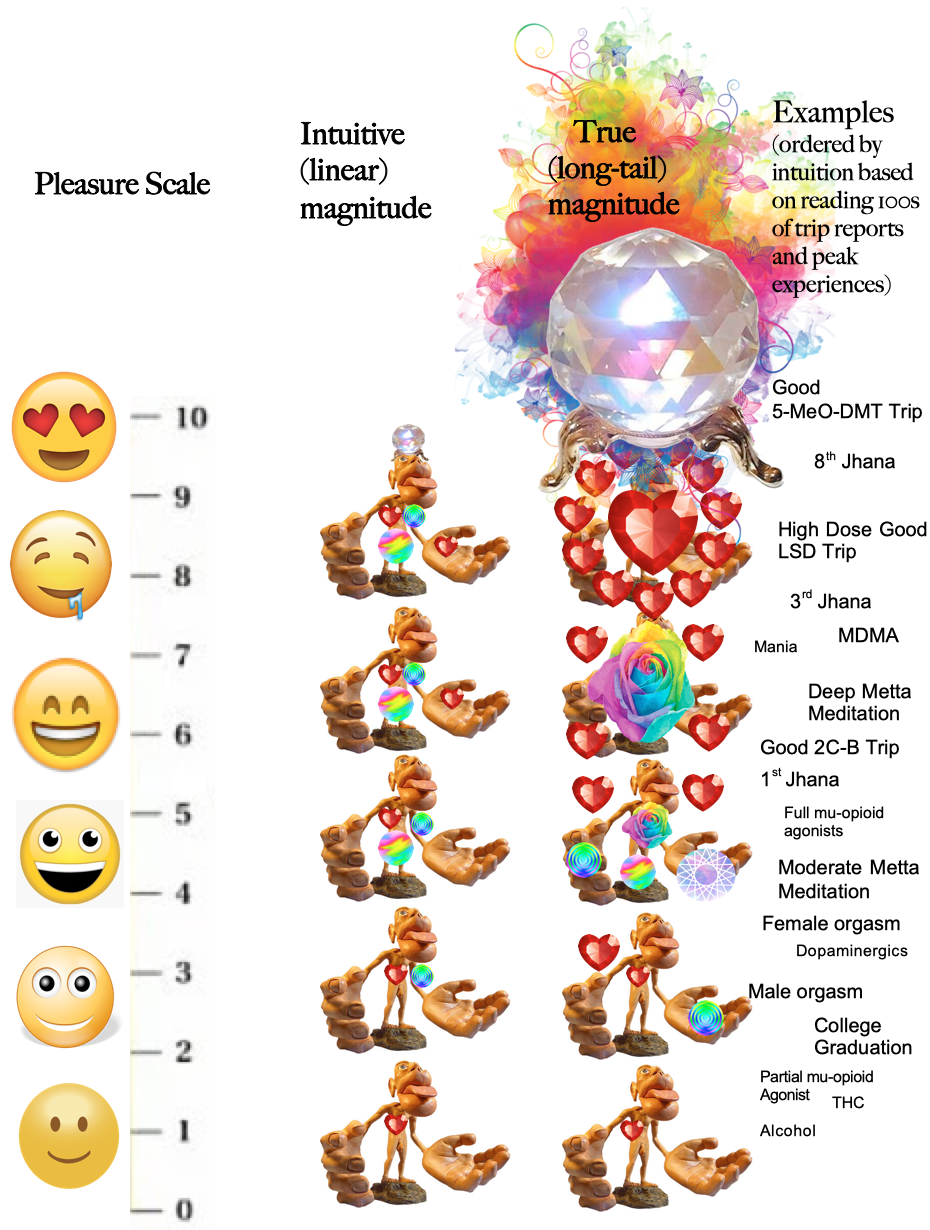

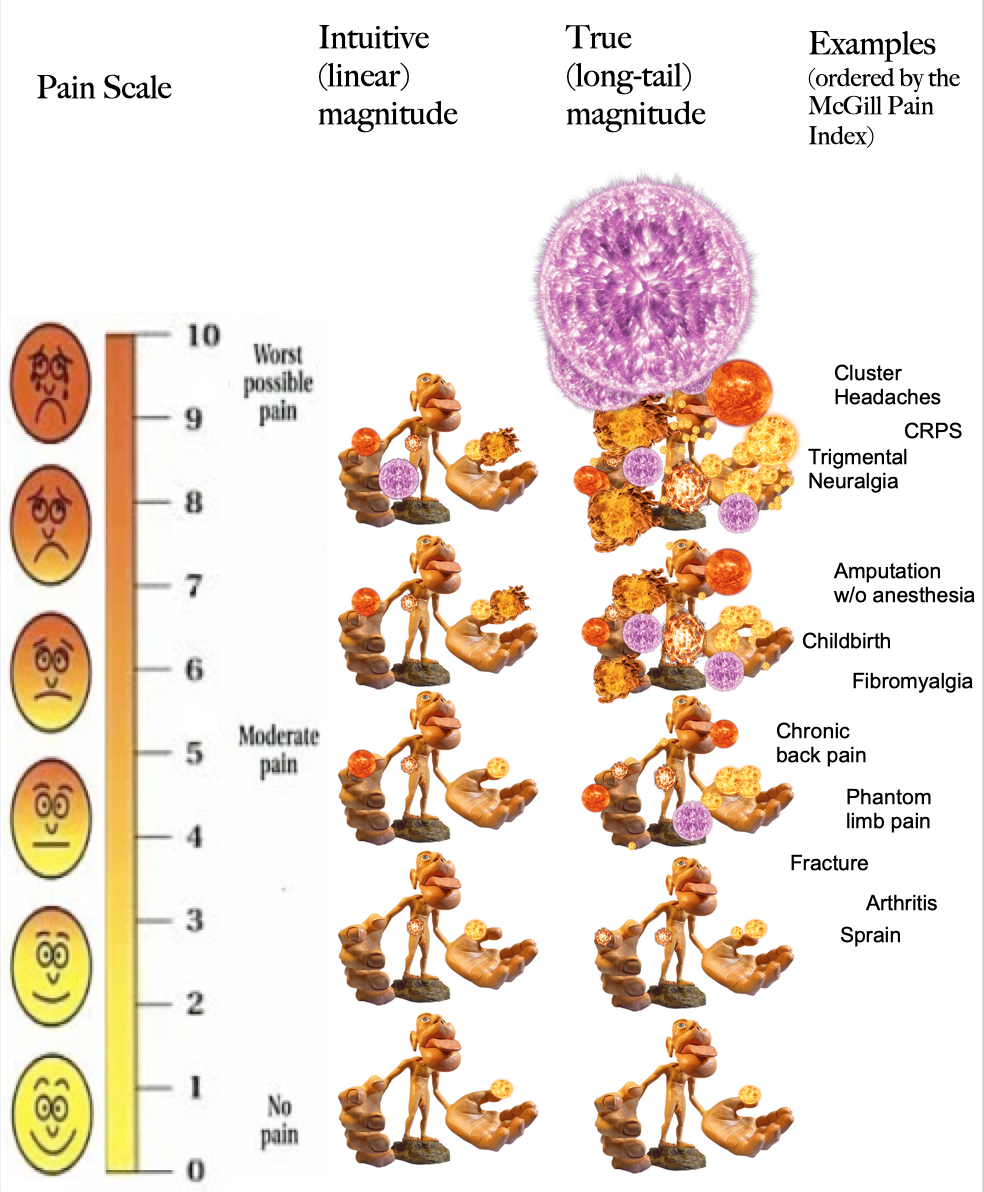

I think we should act extremely responsibly towards those heavily valenced moments of experience, not caring tends to hurt later, a lot. Most people will recognize that driving drunk is really dumb and irresponsible, the same for fighting against a mugger who has a knife when you don’t, but I think we should apply that sober seriousness and carefulness towards many other things, also taking into consideration the fact that the worst and best things have exponentially more (dis)value than the things we usually experience, as Andrés Gómez Emilsson writes in Logarithmic Scales of Pleasure and Pain: Rating, Ranking, and Comparing Peak Experiences Suggest the Existence of Long Tails for Bliss and Suffering.

Fven though we may imagine experiences experiences grow in intensity linearly, there are many reasons to believe that they actually do so exponentially.

For someone living 20,000 years ago, many things we care about today, say our grades at school or interactions through social media, would probably be extremely alien and unexpected. I would argue that after taking a sober and serious look into the actual nature of value and letting that honestly update the things we prioritize and ways in which we act, one also ends up with a pretty different way of looking at the world and about what one should do, which can be pretty unexpected. Now one starts to spend a lot of time trying to find ways in which to abort cluster headaches, ways in which to better treat chronic pain, or one starts seeing the incredibly and extremely horrible things that happen in factory farming through a lens different from the usual human one in which it just looks like something far away that is through some sketchy logic, justified, we even start doubting the ways in which we should act upon the existence of wild animal suffering, and we start to care a lot more about trying to make our future go in good ways, amongst many other things.

Imagine there was someone who had a button which activated a machine that would cut his finger 10 minutes after pressing it but they had a tiny bit of fun while pressing it and they willingly chose to press it, clearly not very smart, who in their right mind would press that? I would argue though that this category of problems also includes the type of things mentioned above, people take decisions based on their immediate desires and not considering the effect that may have on other places/moments.

An important view to add into this is the lens from personal identity. How can we be so sure that we are an separate and independent self that survives over time? what is that which would carry our identity over time? our memories? they are not wormholes into the past, only shapes our brain takes which make representations of things that have happened to us reappear in our experience, plus if someone had the same memories would they automatically be the same entity as you somewhere else? why? if you lost your memories would you suddenly become a different entity? memories aren’t fundamental entities, they are just particular structures in our brain, our atoms are also changing all the time, the same for the shapes of our brain/body (which, as I said, aren’t actually fundamental, two squares with the same width and height aren’t the same entity despite sharing their shape), I would argue that it is not possible to find such a constant «only yours» carrier of identity, and that if we are willing to accept that what we are survives over time, we’d have to also accept that that carrier of identity is the same for all beings, (your atoms once were inside of a star and once may have belonged to another animal, the same for everything that forms you), also there’s the view that sees the universe as one field, which has many segments like the one we are, amongst many other arguments that I won’t mention here. Arguably we should seriously consider the idea that we are actually deep down only one being, or at least that we aren’t actually individuals in the way we usually assume we are, although this unusual views over personal identity may seem like just esoteric stuff that you see revealed on psychedelics and not something out of a scientific, sober understanding, the view of open individualism «we are all one» has been defended by many famous thinkers whose thinking we wouldn’t consider just woo (off course this isn’t necessarily an argument to immediately give it credibility but it’s worth noting), like Arthur Schopenhauer, Erwin Schrödinger and Freeman Dyson amongst many others, and I think that after deeply thinking about the subject, it fits very well into a scientific rationalistic way of looking at reality.

It can be argued that the suffering of a pig in a slaughterhouse, or of someone having a cluster headache is actually our own, so why make/let ourselves suffer? why shouldn’t we act with the same responsibility we already give many things, to avoid bad stuff happening to beings that probably are only illusorily different from us?. Also, even ignoring this view you can notice that all experiences are equally real and ultimately just expressions of the same universe, I think it’s extremely hard to find a reason why your experience would somehow be more important than the rest just because of it being yours.

I’d say that we should not let horrible stuff keep happening, we should act to reduce it as much as it is possible, and save ourselves.

Deja un comentario